Boggo Road Gaol, Brisbane

Now a heritage site, the listed Brisbane Jail, or Boggo Road Gaol, which closed in 1989 had a reputation of being haunted. The ghost is said to be Ernest Austin who was executed on 22 September 1913 for the rape and murder of Ivy Mitchell at Cedar Creek Road, near Samford.

The following article by Jonno Nash was published in the Herald Sun on 30 May 2014.

A HAUNTING image of a Victorian child killer who still torments one of Australia’s most notorious jails has emerged more than a century after he swung from a noose.

Ernest Austin, also known as Ernest Johnson, was the last of 42 inmates hanged at Queensland’s notorious Boggo Road Gaol.

He was hanged for the brutal murder of 11-year-old Ivy Alexandra Mitchell.

But it’s Austin’s harrowing supernatural presence — not his horrific crime — that has cemented his name into prison folklore.

It is said that after the burly 23-year-old dropped through the gallows trapdoors in September 1913, fellow inmates of A Wing, the site of Austin’s execution, were tormented by paranormal experiences.

Austin’s ghost would materialise through the concrete walls, pass through the jail’s dilapidated corridors and throttle prisoners in their cells at the Dutton Park penitentiary, just 4km south of Brisbane’s CBD.

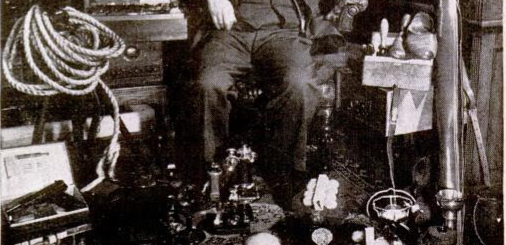

Now pictures of the killer held for decades in the archives of Victoria’s Public Record Office can be seen for the first time.

They show Austin as a young prisoner held in Melbourne Gaol for the brutal attempted rape of a 12-year-old girl.

But it was after his execution that Austin’s haunting legacy grew, as veteran prisoners and guards warned new inmates of the murderer’s stalking apparition, and his mission to harvest souls for the devil.

They said Austin’s ghost struck a pact with Satan to meet a quota of souls to avoid his own fiery doom in hell.

And if anyone deserved to go to hell, Austin certainly did.

The story behind the rise of his evil spectre begins in a different time. The night of June 8, 1913, to be exact — when little Ivy Alexandra Mitchell, 11, went missing.

Ivy’s body was found in dense scrub at the local state school, several kilometres from the family farm in Samford, a rural community northwest of Brisbane.

When dusk broke and Ivy hadn’t returned from a day spent with friends, her worried father and brother grabbed a lantern and began searching the nearby school.

A pair of large hobnailed boot prints alongside smaller barefoot prints were found leading into bushland.

At a certain point the little tracks stopped, but the boots plodded on into the bush.

As they followed the tracks through the heavy shrub, the Mitchells faced a grim revelation.

Farmer Mitchell found his girl lying a pool of blood, with her throat “fearfully cut” and with “unmistakable signs that the child had been foully murdered”.

Ernest Austin, the Mitchells’ farmhand, was the prime suspect and was taken to the scene the next day by local authorities.

An investigation revealed Austin’s boots matched the markings near the crime scene.

When the white sheet covering Ivy was peeled back, Austin glanced at the battered body and said, “I don’t know her.”

Austin’s unflinching reaction to the gruesome site struck a suspicious chord with police.

The fact that before this heinous crime, Austin had served time in Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge for attempted rape did nothing to reduce their instinct that they had their man.

It transpired Austin had a long history of run-ins with the police, and even as a child was sentenced to the care of the Victorian Neglected Children’s Department.

Four years earlier, the most serious of his brushes with the law came in September 1909, when he attacked a 12-year-old girl in an attempt to rape her.

The incident has a chilling similarity with Ivy’s murder.

According to Innocence Lost — the Last Man Hanged in Queensland, his poor victim Louisa Adelaide Champion was lured into a wash house where the axe-wielding fiend gagged her, grabbed her by the throat and threatened to kill her.

Her screams brought help, which scared him off, but there were witnesses and it didn’t take long for police to track Austin down.

He was sentenced to four years inside the old Melbourne Gaol.

And while the warning signs were there, Austin’s tendencies didn’t change when he left Victoria and headed to New South Wales and then Queensland.

It was in Queensland that he found work as a farmhand near the site of his awful deed.

It would become clear, after a colourful bouquet was found near the girl’s corpse, that the labourer had lured Ivy into the sparse fields.

Austin, while toiling the family’s fields, was regularly seen picking flowers with Ivy.

At the time, the Brisbane Courier described the act as “one of the most horrible and abhorrent in the annuals of Australian crime”, and noted his “callous indifference’’ and “silly grin” in court.

After the jury’s six-hour deliberation, Chief Justice Sir Pope Cooper ordered Austin “to be hanged by the neck until you are dead and may the Lord have mercy on your soul”.

The Courier’s reports of his hanging on September 22, 1913, noted he “went to his doom quietly and firmly and with a resignation which indicated complete spiritual submission and comfort’’.

“I say straight out that I highly deserve this the punishment,’’ he said, as he waited for his fate.

And then he apologised to his Ivy’s father and his own mother before crying out: “God Save the King’’.

He told Boggo Road’s chief warder to wire his mother that he “died happy and without fear’’

But other long-serving crooks begged to differ with the account, instead recalling a crazed morphine-induced Austin laughing madly until the executioner pulled the lever and ended his torment.

Later, fellow convicts would describe the evil laughter echoing off the prison walls in the early mornings.

Other outlaw raconteurs gave eerie descriptions of a roaring spiritual shriek that had emerged from the shadows of the gallows as Austin was hanged.

The awful scream of despair was described in a popular 1950s Brisbane newspaper, The Truth, which wrote of “a spinechilling ethereal acknowledgment that Austin’s little girl victim was being avenged and justice was being one”.

Prison guards said it was the sounds of the rejoicing victims or a high-pitched eruption by hanged criminals welcoming Austin to the next passage.

Whatever the theory, the ghost of Boggo Road’s 42nd executed jailbird looks set to survive — at least in the imagination.

After 119 years, Boggo Road is now closed as a jail, but tourists still spook themselves by stepping into the cramped cells or spotting a silhouette of a man on the upper floors and beneath the stairs at E Wing.

In the Courier Mail in 1979, jail employee Bob Smith played down the legend as a fearmongering myth for new convicts.

“Every couple of years some old wag tells a young prisoner that if he looks at the wall in A Wing, where the gallows used to be, he’ll see the famous jail ghost on a dark blustery night,” Smith said.

“Of course he’ll see the wavering reflection from one of the prison lights blowing in the breeze.

“We mightn’t have the most modern prison in Australia — yet — but we don’t scrimp in electricity.”

But historian Jack Sim, publisher of Innocence Lost — the Last Man Hanged in Queensland, professes to be among the witnesses, and is adamant the ghost is no myth.

His obsession with Boggo Rd’s dreadful past has seen him chronicle Austin’s criminal life from his humble Warrnambool beginnings, his awful crimes and his ghostly revival as publisher of Innocence Lost: The Last Man Hanged at Boggo Road, published late last year.

“I’ve always felt that this is one of Australia’s great prison stories,” Mr Sim said.

“And of the 42 people executed at Boggo Rd, Austin was one of the worst.”

Recent Comments