The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Hill

Around the time of the crusades (in some accounts) in the area around the river Wear, there is a tale told about a fearsome dragon, which terrorised the area and was dispatched with cunning by a brave warrior.

John Lambton, the young heir to Lambton Hall, was fishing on the river Wear one Sunday morning, while all the other villagers and castle residents were at mass in Brugeford Chapel. After a couple of hours of catching nothing, his hook was caught by something powerful and quick, thinking that he had hooked a great fish he set about landing the catch. He toiled for what seemed an age, and finally pulled his prize on the sandy bank.

He had caught a black worm like creature, which was only small, but twisted and coiled with great power. In appearance the creature was completely black, with the head of a salamander and needle sharp teeth. It seemed to secrete a sticky slime, and had nine holes along each side of its mouth. Cursing, he wondered what to do with the creature when an old man appeared from behind him, he asked the young Lambton what he had caught, and looking at the creature the old man crossed himself. He warned Lambton not to throw the creature back into the river. “It bodes no good for you but you must not cast it back into the river, you must keep it and do with it what you will.” At this the old man walked away disappearing as quickly as he had appeared.

John Lambton picked up the creature and put it into his catch basket, walking home he mulled over the stranger’s words and looked again at the hideous thing lying in his basket. A feeling of unease swept over him and he threw the catch into an ancient well on the road back to the hall (the well was forever after known as Worms Well).

The years passed and John Lambton went off to the crusades, with every passing year the worm grew in strength in its deep dark hole. The well became unusable as the water became poisoned, strange venomous vapours were seen rising out of the well, and village gossip surmised that the well had been cursed, and that something unworldly lived in its depths. One morning the village gossip was answered, during the night the worm, now in full maturity, had slipped out of the well and wrapped itself three times around a rocky island in the middle of the river, a trail of black slime outlined its path from the well.

The morning was a hive of activity as the news spread throughout the village and to neighbouring farms. Those brave enough went as close as they dared to get a glimpse of the creature. The dragon had no legs or wings, but a thick muscled body that rippled as it moved. Its head was large and its gaping maw bristled with razor sharp teeth, venomous vapours trailed from its nostrils and mouth as it breathed.

]For a short time the dragon did nothing, during the day it stayed in mid stream and at night it came back to land and coiled itself three times around a nearby hill, leaving spiral patterns in the soft earth. This lull was short lived, for soon the beast became hungry and started to rampage around the countryside, always returning to its hill or Worms Rock in the river Wear. Depending on the account, the hill the worm returned to was either Penshaw Hill or, the aptly named Worm Hill in nearby Fatfield.

]For a short time the dragon did nothing, during the day it stayed in mid stream and at night it came back to land and coiled itself three times around a nearby hill, leaving spiral patterns in the soft earth. This lull was short lived, for soon the beast became hungry and started to rampage around the countryside, always returning to its hill or Worms Rock in the river Wear. Depending on the account, the hill the worm returned to was either Penshaw Hill or, the aptly named Worm Hill in nearby Fatfield.

It took small lambs and sheep and ate them whole, and it tore open cows udders with its razor teeth to get at the milk, which it could smell from miles away.

The dragon became bolder and bolder, some brave villagers tried to kill the beast but where crushed and drowned in the river, or torn to pieces with its razor fangs.

Eventually the dragon came to Lambton Hall, where the lord lived on his own. Fortunately the local residents rallied at the hall, and were ready for its coming. They filled a large stone trough with warm milk from the nine kye of the byre. The dragon came to the hall gates but was distracted by the smell of the milk. It plunged into the trough and drained it dry, thus sated the dragon returned to its river abode.

Thus began a ritual that was not to be abated for seven years. The dragon stopped its roaming in the village and left the cows and the sheep alone. It only ventured up the lane to the hall for its daily offering of milk. As the years passed the trail became marked by a path of dark slime and the villagers returned to the village in some semblance of normality. Every so often people from far and wide would come to kill the dragon but would always meet the same fate as those early villagers.

After seven years had passed, John Lambton returned from the crusades a powerful and seasoned knight. When he heard of the plight of his village he devised plan to kill the beast. He went to the wise woman who lived in Brugeford to gain her advice. She told him that the plight of the village was his fault and that it was his duty to remedy the situation: You and you alone can kill the worm, go to the blacksmith, and have a suit of armour wrought with razor sharp spear heads studded throughout its surface. Then go to the worm’s rock and await its arrival. But mark my words well, if you slay the beast you must put to death the first thing that crosses your path as you pass the threshold of Lambton Hall. If you do not do this then three times three generations of Lambtons will not die in their beds.

John listened to the advice and swore an oath to complete it. He then went to the local blacksmith and had him forge a suit of armour embedded in double-edged spikes, and spent the night in the local chapel.

During the next day John Lambton, clad in the specially made armour engaged in battle with the dragon in midstream. Every time the dragon tried to embrace him it cut itself to ribbons on the spikes, so that pieces of its flesh were sliced off and floated down the river on a crimson tide. Eventually the worm grew so weak that he could despatch it with one heavy sword blow to its head.

He then let out three blasts on his bugle to tell of his victory, and as a signal for the servants to release his favourite hound from the house to complete his vow. Unfortunately the servants forgot in the commotion and joy, and as John passed over the threshold of the hall his father rushed out to greet him. Dismayed John blew another blast on his horn and the servants released the hound, which John killed with one sweeping blow from his sword. But it was too late, the vow was broken and for generations after none of the Lambtons died in their beds. It is said that the last one died while crossing over Brugeford Bridge over a hundred and forty years ago.

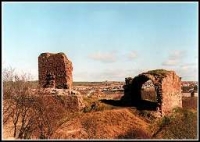

Penshaw Hill

Penshaw Hill

One of the hills the worm is said to have frequented is actually the site of the only triple rampart, Iron Age hill fort known in the North of England. The spiral patterns or furrows suggested by the legend as being formed by the worm coiling itself thrice around the hill, could in fact be the triple ramparts of the hill fort. The hill is also known for the prominent landmark of Penhsaw Monument, a folly based on a Greek temple.

The Lambton Worm – Traditional Folksong Based on the Legend

One Sunday morn young Lambton

Went a-fishin’ in the Wear;

He catched a fish upon his heuk,

He thowt leuk’t varry queer,

But whatt’na kind of fish it was

Young Lambton couldna tell.

He waddna fash to carry hyem,

So he hoyed it in a well.

Chorus:

Whisht! lads, haad ya gobs,

Aa’ll tell ye aall an aaful story,

Whisht! lads, haad ya gobs,

An aa’ll tell ye ‘boot the worm.

Noo Lambton felt inclined to gan

An’ fight in foreign wars.

He joined a troop o’ Knights

That cared for neither wounds nor scars,

An’ off he went to Palestine

Where queer things befel,

An’ varry seun forgot aboot

The queer worm in the well.

(Chorus)

But the worm got fat an’ graad an’ graad,

An’ graad an aaful size;

With greet big teeth, and greet big mooth,

An’ greet big goggley eyes.

An’ when at neets he craaled ‘oot

To pick up bits o’ news,

If he felt dry upon the road,

He milked a dozen coos.

(Chorus)

This feorful worm wad often feed

On calves an’ lambs an’ sheep

An’ swally little bairns alive

When they laid doon to sleep.

An’ when he’d eaten aall he cud

An’ he had had his fill,

He craaled away an’ lapped his tail

Seven times roond Pensher Hill.

(Chorus)

The news of this most aaful worm

An’ his queer gannins on,

Seun crossed the seas, gat to the ears

Of brave an’ bowld Sir John.

So hyem he cam an’ catched the beast

An’ cut ‘im in three halves,

An’ that seun stopped him eatin’ bairns

An’ sheep an’ lambs and calves.

(Chorus)

So noo ye knaa hoo aall the folks

On byeth sides of the Wear

Lost lots o’ sheep an’ lots o’ sleep

An’ lived in mortal feor.

So let’s hev one to brave Sir John

That kept the bairns frae harm,

Saved coos an’ calves by myekin’ halves

O’ the famis Lambton Worm.

(Final Chorus)

Noo lads, Aa’ll haad me gob,

That’s aall Aa knaa aboot the story

Of Sir John’s clivvor job

Wi’ the aaful Lambton Worm.

Re: The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Hill

The Haunted Homes and Family Traditions of Great Britain by John Ingram (1897)

At Lambton Castle, in Durham, there is shown the figure of a man in armour, cut in stone, having something like razors set in his back-plate. He is represented in the act of thrusting his sword down the throat of a dragon or serpent. The tradition which is typified by this ancient figure, and which for centuries has been identified with the Lambton family, now represented by the Earl of Durham, is one of the most singular and notorious in England. Burke, in his Vicissitudes of Families, gives the tale at some length, but derives it chiefly from Surtees, the historian and antiquary, and from him, with some few additional particulars from other local authorities, we purpose giving it in a somewhat abridged form.

According to the old legend the Lambtons "were so brave that they feared neither man nor God," and, apparently, had no respect for the Sabbath. One Sunday, therefore, the reckless heir of the race, according to his profane custom, went to fish in the river Wear, and, after trving his piscatorial skiU for a long time without success, vented his disappointment in curses loud and deep, much to the distress of passers hy on their road to church. At length his luck appeared as if about to change, for he felt something struggling at the end of his line. Pulling it carefully to land, in expectation of capturing a great fish, he was wofully disappointed and enraged to find it was a worm or snake, of repulsive appearance. He cleared it from his hook, and flung it into an adjacent well, remarking to a passer-by that he thought he had caught the devil, and requesting his opinion on the strange animal. The stranger, after looking into the well, remarked that he had never seen anything like it before, that it was like an eft, but that it had nine holes on each side of its mouth, and opined that it betokened no good.

After a while, the heir of the Lambtons repented of his evil courses, and proceeded to a distant land, in order to wage war against the infidels. During the seven long years that he was absent from home, a most distressing and unexpected state of affairs had come to pass. The worm or serpent, which he had flung into the well on that desecrated Sabbath, had grown so large that it had to seek another and more capacious place of residence. The locality which it selected as its favourite abode was a small hill near the village of Fatfield, on the north side of the river Wear, about a mile and a half below Lambton Castle; and at last, so great was its length, and so great was its strength, that it could, and would, wind itself round this hill, which is upwards of throe hundred yards in circumference, in a triple cord, in such a manner that traces of its folds have remained almost to within memory of the last generation. It became a terror to the whole country, committing all kinds of devastation on the flocks and herds, arid poisoning the pasture with its reeking breath. In vain did the knights and gentlemen thereabouts endeavour to slay this monster, it was a match for the best of them, always leaving them minus life or limb ; for although many of them had succeeded in cutting it asunder, the severed parts had reunited immediately, and the worm remained whole as before the conflict.

Finally, the heir of Lambton returned from the wars; he was naturally distressed to learn of the desolation of his ancestral lands, and still more so when he discovered that the cause of all the misery was really due to the monster he had drawn to land on the long bygone desecrated Sabbath. He determined, at all risks, to endeavour to destroy the monster; but as all previous adventurers had failed, he deemed it best, before undertaking the conflict, to consult a witch or wise woman as to the best method of proceeding. Accordingly, he applied to a witch, and, after having been reproached as the cause of all the misery brought upon the country, she advised him how to act. He was directed to provide himself with a coat of armour covered with razors, and, by means of that and his trusty sword, promised success, that is to say, conditionally upon his making a solemn vow to kill the first living thing which he should meet after slaying the worm. Lambton agreed to the conditions ; but was informed that if he failed to keep his word, the "Lords of Lambton for nine generations should not die in their beds," no very great hardship, it might be deemed, for that martial age.

According to his instructions, the knight had a suit of armour covered with razors made, and having donned this, he instructed his aged father that when he had destroyed the worm, he would blow three blasts upon his horn as a signal of his victory, whereupon his favourite greyhound was to be let loose, so that it might run to him, and therefore be the first thing that would meet him, and thus be slain in fulfilment of his agreement with the witch. The father promised and gave his blessing, and young Lambton, having made the vow enjoined, started on his dangerous expedition. As soon as he approached the hill round which the worm was coiled, it unwound itself and came down to the riverside to attack him. Nothing daunted by its hideous aspect, the knight struck at it with might and main, yet without appearing to make any impression upon it beyond increasing its rage. It now seized its opponent in its horrid folds and sought to strangle him; but the more tightly it grasped him, the more frightfully was it wounded, the razor blades cutting it through and through. But as often as the monster fell to the ground cut by the knight’s terrible coat of mail, as often, says the legend, did the severed pieces re-unite, and the wounds heal up. Lambton, seeing that the worm was not to be destroyed in this way, stept into the river Wear, whither the monster followed him. The change of position proved fatal to the worm, for as fast as the pieces were cut off by the razors they were carried away by the stream, and the monster, being unable to re-unite itself was, after the desperate conflict, at last utterly destroyed.

As soon as Lambton had achieved the victory, he blew three blasts upon his horn; but his father, in the excitement of the moment, forgot to have the greyhound unloosened, and in his impatience ran out of the castle to greet his son, and was the first living being that met his gaze. The knight embraced his father, and again blew his horn, upon which the hound was let loose, and, running towards Lambton, was slain. But this was too late to retrieve matters, his vow having enjoined the slaying of the first living creature that he should meet with, and his father had been the first to meet him. So the curse was on the house of Lambton, and for nine generations not one of its lords could die in his bed.

Sir Bernard Burke points out that popular tradition races the curse back to Robert Lambton, who died without issue in 1442, leaving the estates to his brother Thomas, but bequeathing by his will to his " brother, John Lambton, knight of Rhodes, 100 marks." In an ancient pedigree this John Lambton, knight of Rhodes, is described as he " that slew the worm," and as " Lord of Lambton after the death of four brothers without male issue." His son Robert is said to have been drowned at Newbrig, near the chapel where the knight had registered his rash and unperformed vow, and tradition specifies a bedless death for each successive nine generations of the Lords of Lambton. After adverting to the various ways and places in which different heirs of Lamb ton met with death, our chief authority for this portion of the legend concludes:

Great curiosity prevailed in the life-time of Henry to know if the curse would " hold good to the end." He died in his chariot, crossing the new bridge, in 1761, thus giving the last connecting link to the chain of circumstantial evidence connected with the history of the worm of Lambton. His succeeding brother, General Lambton, who lived to a great age, fearing that the prophecy might be possibly fulfilled by his servants, under the idea that he could not die in his bed, kept a horsewhip beside him in his last illness, and thus eluded the prediction. Although the spell put on this ancient family by the witch is said to have been broken by the death of Henry Lambton in 1761, yet neither of the two last lords have died at home, and this, to the knights of ancient times, says Burke, " would have been sorer punishment than dying in the battle-field, for they loved to sleep in their own country and with their fathers."

Re: The Lambton Worm and Penshaw Hill

English Fairy and Other Folk Tales by Edwin Sidney Hartland [1890]

THE LAMBTON WORM. (1)

THE park and manor-house of Lambton, belonging to a family of the same name, lie on the banks of the Wear, to the north of Lumley. The family is a very ancient one, much older, it is believed, than the twelfth century, to which date its pedigree extends. The old castle was dismantled in 1797, when a site was adopted for the present mansion on the north bank of the swiftly-flowing Wear, in a situation of exceeding beauty. The park also contains the ruins of a chapel, called Brugeford or Bridgeford, close to one of the bridges which span the Wear.

Long, long ago–some say about the fourteenth century–the young heir of Lambton led a careless, profane life, regardless alike of his duties to God and man, and in particular neglecting to attend mass, that he might spend his Sunday mornings in fishing. One Sunday, while thus engaged, having cast his line into the Wear many times without success, he vented his disappointment in curses loud and deep, to the great scandal of the servants and tenantry as they passed by to the chapel at Brugeford.

Soon afterwards he felt something tugging at his line, and trusting he had at last secured a fine fish, he exerted all his skill and strength to bring his prey to land. But what were his horror and dismay on finding that, instead of a fish, he had only caught a worm of most unsightly appearance I He hastily tore the thing from his hook, and flung it into a well close by, which is still known by the name of the Worm Well.

The young heir had scarcely thrown his line again into the stream when a stranger of venerable appearance, passing by, asked him what sport he had met with; to which he replied: “Why, truly, I think I have caught the devil himself. Look in and judge.” The stranger looked, and remarked that he had never seen the like of it before; that it resembled an eft, only it had nine holes on each side of its mouth; and, finally, that he thought it boded no good.

The worm remained unheeded in the well till it outgrew so confined a dwelling-place. It then emerged, and betook itself by day to the river, where it lay coiled round a rock in the middle of the stream, and by night to a neighbouring hill, round whose base it would twine itself; while it continued to grow so fast that it soon could encircle the hill three times. This eminence is still called the Worm Hill. It is oval in shape, on the north side of the Wear, and about a mile and a half from old Lambton Hall.

The monster now became the terror of the whole country side. It sucked the cows’ milk, worried the cattle, devoured the lambs, and committed every sort of depredation on the helpless peasantry. Having laid waste the district on the north side of the river, it crossed the stream and approached Lambton Hall, where the old lord was living alone and desolate. His son had repented of his evil life, and had gone to the wars in a distant country. Some authorities tell us he had embarked as a crusader for the Holy Land.

On hearing of their enemy’s approach, the terrified household assembled in council. Much was said, but to little purpose, till the steward, a man of age and experience, advised that the large trough which stood in the courtyard should immediately be filled with milk. This was done without delay; the monster approached, drank the milk, and, without doing further harm, returned across the Wear to wrap his giant form around his favourite hill. The next day he was seen recrossing the river; the trough was hastily filled again and with the same results. It was found that the milk of “nine kye” was needed to fill the trough; and if this quantity was not placed there every day, regularly and in full measure, the worm would break out into a violent rage, lashing its tail round the trees in the park, and tearing them up by the roots.

The Lambton Worm was now, in fact, the terror of the North Country. It had not been left altogether unopposed. Many a gallant knight had come out to fight with the monster, but all to no purpose; for it possessed the marvellous power of reuniting itself after being cut asunder, and thus was more than a match for the chivalry of the North. So, after many conflicts, and much loss of life and limb, the creature was left in possession of its favourite hill.

After seven long years, however, the heir of Lambton returned home, a sadder and a wiser man–returned to find the broad lands of his ancestors waste and desolate, his people oppressed and well-nigh exterminated, his father sinking into the grave overwhelmed with care and anxiety.

He took no rest, we are told, till he had crossed the river and surveyed the Worm as it lay coiled round the foot of the hill; then, hearing how its former opponents had failed, he took counsel in the matter from a sibyl or wise woman.

At first the sibyl did nothing but upbraid him for having brought this scourge upon his house and neighbourhood; but when she perceived that he was indeed penitent, and desirous at amy cost to remove the evil he had caused, she gave him her advice and instructions. He was to get his best suit of mail studded thickly with spear-heads, to put it on, and thus armed to take his stand on the rock in the middle of the river, there to meet his enemy, trusting the issue to Providence and his good sword. But she charged him before going to the encounter to take a vow that, if successful, he would slay the first living thing that met him on his way homewards. Should he fail to fulfil this vow, she warned him that for nine generations no lord of Lambton would die in his bed.

The heir, now a belted knight, made the vow in Brugeford chapel He studded his armour with the sharpest spear-heads, and unsheathing his trusty sword took his stand on the rock in the middle of the Wear. At the accustomed hour the Worm uncoiled its “snaky twine,” and wound its way towards the hall, crossing the river close by the rock on which the knight was standing eager for the combat. He struck a violent blow upon the monster’s head as it passed, on which the creature, “irritated and vexed,” though apparently not injured, flung its tail round him, as if to strangle him in its coils.

In the words of a local poet–

“The worm shot down the middle stream

Like a flash of living light,

And the waters kindled round his path

In rainbow colours bright.

But when he saw the armed knight

He gathered all his pride,

And, coiled in many a radiant spire,

Rode buoyant o’er the tide.

When he darted at length his dragon strength

An earthquake shook the rock,

And the fireflakes bright fell round the knight

As unmoved he met the shock.

Though his heart was stout it quailed no doubt,

His very life-blood ran cold,

As round and round the wild Worm wound

In many a grappling fold.”

Now was seen the value of the sibyl’s advice. The closer the Worm wrapped him in its folds the more deadly were its self-inflicted wounds, till at last the river ran crimson with its gore. Its strength thus diminished, the knight was able at last with his good sword to cut the serpent in two; the severed part was immediately borne away by the swiftness of the current, and the Worm, unable to reunite itself, was utterly destroyed.

During this long and desperate conflict the household of Lambton had shut themselves within-doors to pray for their young lord, he having promised that when it was over he would, if conqueror, blow a blast on his bugle. This would assure his father of his safety, and warn them to let loose the favourite hound, which they had destined as the sacrifice on the occasion, according to the sibyl’s requirements and the young lord’s vow. When, however, the bugle-notes were heard within the hail, the old man forgot everything but his son’s safety, and rushing out of doors, ran to meet the hero and embrace him.

The heir of Lambton was thunderstruck; what could he do? It was impossible to lift his hand against his father; yet how else to fulfil his vow? In his perplexity he blew another blast; the hound was let loose, it bounded to its master; the sword, yet reeking with the monster’s gore, was plunged into its heart; but all in vain. The vow was broken, the sibyl’s prediction fulfilled, and the curse lay upon the house of Lambton for nine generations.

________________________________________

Footnotes

1) Henderson’s Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties, p. 287.