Wren Day

Wren Day is celebrated on St Stephens Day (26 December) and generally comprised of a wren being killed, attached to a pole and presented on doorsteps within the township by wrenboys, singing a rhyme and asking for money to pay for the funeral of the bird. One of the feathers, which are thought to be lucky would be given to any household contributing. The tradition is now on the wane and in more modern times the wren was caught and carried unharmed in a net or box and today a fake wren is used. The wrenboys/mummers celebrate the wren and are sometimes dressed in straw outfits and masks, parading through the towns and villages playing music.

Sir James George Frazer gives the following account in his The Golden Bough (1922) of the Wren Hunt and attached folklore. “The custom of annually killing the wren has prevailed widely both in this country and in France. In the Isle of Man down to the eighteenth century the custom was observed on Christmas Eve, or rather Christmas morning. On the twenty-fourth of December, towards evening, all the servants got a holiday; they did not go to bed all night, but rambled about till the bells rang in all the churches at midnight. When prayers were over, they went to hunt the wren, and having found one of these birds they killed it and fastened it to the top of a long pole with its wings extended. Thus they carried it in procession to every house chanting the following rhyme:

“We hunted the wren for Robin the Bobbin,

We hunted the wren for Jack of the Can,

We hunted the wren for Robin the Bobbin,

We hunted the wren for every one.”

When they had gone from house to house and collected all the money they could, they laid the wren on a bier and carried it in procession to the parish churchyard, where they made a grave and buried it “with the utmost solemnity, singing dirges over her in the Manks language, which they call her knell; after which Christmas begins.” The burial over, the company outside the churchyard formed a circle and danced to music.

A writer of the eighteenth century says that in Ireland the wren “is still hunted and killed by the peasants on Christmas Day, and on the following (St. Stephen’s Day) he is carried about, hung by the leg, in the centre of two hoops, crossing each other at right angles, and a procession made in every village, of men, women, and children, singing an Irish catch, importing him to be the king of all birds.” Down to the present time the “hunting of the wren” still takes place in parts of Leinster and Connaught. On Christmas Day or St. Stephen’s Day the boys hunt and kill the wren, fasten it in the middle of a mass of holly and ivy on the top of a broomstick, and on St. Stephen’s Day go about with it from house to house, singing:“The wren, the wren, the king of all birds,

St. Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze;

Although he is little, his family’s great,

I pray you, good landlady, give us a treat.”

Money or food (bread, butter, eggs, etc.) were given them, upon which they feasted in the evening.

In the first half of the nineteenth century similar customs were still observed in various parts of the south of France. Thus at Carcassone, every year on the first Sunday of December the young people of the street Saint Jean used to go out of the town armed with sticks, with which they beat the bushes, looking for wrens. The first to strike down one of these birds was proclaimed King. Then they returned to the town in procession, headed by the King, who carried the wren on a pole. On the evening of the last day of the year the King and all who had hunted the wren marched through the streets of the town to the light of torches, with drums beating and fifes playing in front of them. At the door of every house they stopped, and one of them wrote with chalk on the door vive le roi! with the number of the year which was about to begin. On the morning of Twelfth Day the King again marched in procession with great pomp, wearing a crown and a blue mantle and carrying a sceptre. In front of him was borne the wren fastened to the top of a pole, which was adorned with a verdant wreath of olive, of oak, and sometimes of mistletoe grown on an oak. After hearing high mass in the parish church of St. Vincent, surrounded by his officers and guards, the King visited the bishop, the mayor, the magistrates, and the chief inhabitants, collecting money to defray the expenses of the royal banquet which took place in the evening and wound up with a dance.

The parallelism between this custom of “hunting the wren” and some of those which we have considered, especially the Gilyak procession with the bear, and the Indian one with the snake, seems too close to allow us to doubt that they all belong to the same circle of ideas. The worshipful animal is killed with special solemnity once a year; and before or immediately after death he is promenaded from door to door, that each of his worshippers may receive a portion of the divine virtues that are supposed to emanate from the dead or dying god.’

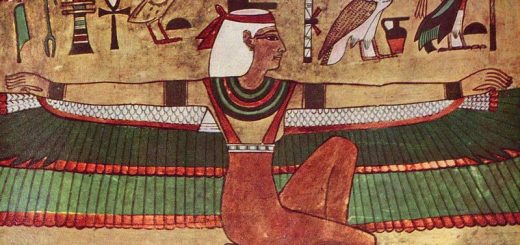

![Manx James [CC0], from Wikimedia Commons – Manx Picture](http://www.mysteriousbritain.co.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/800px-Hunt_the_Wren_Dougla_1904-205x300.jpg)

The following article entitled ‘Flight of the wren boys’ was published in The Irish Times on 15 December 2007.

The wren boys will be out singing and dancing on St Stephen’s Day, but where does this ancient ritual come from, asks Éilís Ní Dhuibhne.

St Stephen’s Day. Driving across Ireland. Damp grey skies over damp green fields. The roads empty, the towns empty. An in-between time. Nothing except peanuts and Nescafé for lunch in the pub in Portlaoise. The very dead of winter.

Toomevara.

“I bet there’ll be wren boys here,” I say to my husband. Sometimes I get these hunches, out of the air. Sometimes I keep them to myself, sometimes I voice them.

Sometimes they’re right.

He looms out of the fog and crosses the main street of Toomevara. Wren boy. Wren man. A hat of thick golden straw, a flowery skirt flapping against his hairy legs. Rubber wellies.

We gasp.

“How did you know?”

Folklorist’s antennae?

Toomevara, Co Tipperary. In the middle of Ireland, the most intriguing part, where strange things happen. There’s something about the sound of that name. Toomevara. And the look of the place. It used to have a great folk museum, in somebody’s garage. You had to get the key from a woman around the corner, who looked very surprised that anyone would ask. Then, you entered a higgledy-piggledy collection of ancient mousetraps, battered churns, chamber pots. A folk museum that could have been an item in a folk museum itself. Like Francis Bacon’s studio in the art gallery, which it resembled in ways.

The big wren boy was followed by a small wren boy. The two of them crossed the road and disappeared. Like otters, like foxes or stoats. Wild things. Glimpsed out of the corner of your eye. They find you, not the other way round.

“For some weeks preceding Christmas, crowds of village boys may be seen peering into the hedges, in search of the “tiny wren”, and when one is discovered the whole assemble and give eager chase, until they have slain the little bird . . . On the anniversary of St Stephen, the enigma is explained. Attached to a huge holly bush, elevated on a pole, the bodies of several little wrens are borne about.”

Thus wrote Mr and Mrs Hall, in Hall’s Ireland: Mr & Mrs Hall’s Tour of 1840. The earliest origins of the custom of “hunting the wren” are unknown, but such customs have been documented since the Middle Ages. The wren is one of the most intriguing of a cycle of Christmas entertainments, which can be simply described as “ritual house visiting”. Groups of people, men and boys, disguised with paint or masks, dressed in unusual clothes, including women’s clothes and usually some garments – dress, or hat – woven from thick golden straw, would go from house to house in a neighbourhood. The Halloween guisers, the trick or treat, is the example that has survived best. The mummers were its most elaborate manifestation – they visited the houses in the weeks before Christmas, performing their traditional death-and-resurrection play. But all the groups, including the wren boys, offered music and song. And they all collected money, which was used to fund a dance or a party when the visits were over. (These days such money is collected for charity.)

THESE HOUSE-VISITING customs were practised throughout northern Europe, in a variety of ways and under many different names – the Mardinsandid in Estonia, Up-Helly-Aa in Shetland, the Mitaartut in Greenland (where they wore masks made of sealskin), to name but a few. Two wonderful studies of the customs, Masks and Mummingin the Nordic Area, edited by Terry Gunnell, and Border Crossing, Mumming in a Cross-Border and Cross-Community Contexts, edited by Séamas Ó Catháin et al, have just been published, and provide comprehensive information and analysis of the customs here and across Europe.

The mummers’ play was performed in the north and eastern parts of Ireland, but the wren boys were much more widespread. Helen Roe, collecting folklore in Co Laois in the 1940s, wrote in Béaloideas, the Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society:

“In all parts of the county the wren boys go their rounds on St Stephen’s Day. During the past thirty years this custom has undergone many changes. Formerly, the bush, usually a holly tree, was decorated with a few rags and the dead body of a wren. It was only carried by boys, and the first group of boys bearing the wren bush were considered to bring luck for the coming year, and in consequence were suitably rewarded . . . “.

She goes on to say that dead birds were rare in her day, the bushes being instead decorated with ribbons and bits of coloured paper. Girls had also begun to join the groups – although even today, in the areas where the custom survives or has been revived, it is predominantly men who dress up as wren boys.

They brought luck. You would rather be visited by them than not, for that reason alone. Luck is always desirable. But so is entertainment, especially in the dead of winter. We can hardly imagine how quiet and wet and dark the countryside used to be, and how welcome musicians and singers would have been to the isolated household. In the days before television, as we say, when all entertainment had to be provided by the community itself, when creativity and performance were the province of everyone, not the celebrated specialist.

In Ireland in the past, Christmas Day was a quiet day when families kept to themselves. On St Stephen’s Day, people would – and are beginning to again – go out and receive visitors at home. The wren boys fulfilled the need people had for company after the quiet of Christmas Day. They re-introduced a sense of carnival into the house. They burst into the kitchen. They sang and played music, they danced with the women. Masked, they could lose their inhibitions. In their dress they crossed gender borders, and they could also, disguised, cross the barriers of their own personalities. Guessing who was behind the masks could give everyone a good laugh:

“The wran, the wran

The King of all birds

On Stephen’s Day

Was caught in the furze.

Although he is little

His family is great

Rise up landlady

And give us a trate.

On with the kettle

And down with the pan

And give us a penny

To bury the wran.”

Alan Gailey, in his classic study, Irish Folk Drama, indicates that the mummers’ play is a survival of ancient fertility magic. The straw used in the costumes symbolises vegetation, carried around in the dead of winter to promise the regrowth of spring.

Sylvia Muller, a French folklorist of renown, in the most comprehensive and analytical study of Irish wren stories and traditions, published in Béaloideas in 1996, similarly underlines the association of the wren boys with fertility and prosperity. Some wren songs end with the lines: ” We wish you a merry Christmas and a happy New Year / With your pockets full of money and your cellar of beer.”

THE STRAW AND holly represent vegetation and the promise of spring. But what about the wren? Where does a small dead bird come into all this? There are various folk explanations of the meaning of the minute bird’s place in the custom, the most common being that the wren betrayed St Stephen, the martyr (and presumably deserves to be killed). Another popular, but very different, “explanation”, is that the wren is the king of all birds and deserves to be carried around and feted. Folk tales about the wren were popular in Ireland, particularly the story in which he outwits the eagle and by a trick becomes the “king of all birds”.

Caoimhe Ní Shúilleabháin, in an article on the wren boys in the Canadian island of Newfoundland (in Border-Crossing) points out that there, where the wren custom was brought by Irish migrants, was originally practised only by boys or very young men, but is now carried out by older men as well. In some areas, there were both adult and juvenile groups in the same area – “na dreoilíní beaga” and the real “dreoilíns”. That the custom was always practised by the young might be one explanation for the centrality of the wren. Dead large birds are, after all, associated with Christmas Day itself.

In Ireland, a goose was ritualistically slaughtered at Martinmas, in November. The killing of the smallest bird by boys on Stephen’s Day contrasts with the killing of a big bird by adults on the days before Christmas. It is likely also that boys or young people might have identified with the little bird, the wren, who was king of the birds in spite of his minute size.

ANOTHER INTERPRETATION IS that the custom has an obvious sexual connotation. Whatever their age, the wren boys were traditionally bachelors; their carrying about of what is almost certainly inter alia a phallic symbol advertises their availability. It doesn’t take much imagination or scholarship to interpret “although he is little his family is great”.

Sylvia Muller’s hypothesis is that the sexual aspect is paramount, that the killing and burial and the wren symbolise the mastery of man over nature, his ability to procreate and thus regenerate. The wren boys’ dances, funded by the money they collected, provided the boys with opportunities to meet partners.

What do the wren boys symbolise nowadays? The custom has been revived in many parts of the country. On December 26th, mummers and wren boys will be out in force; in Dingle-Daingean they will process down Goat Street; on Sandymount Green they will sing and entertain. Possibly what they represent for us is a connection with the past, a link to a way of life that is gone, even a link to nature and the countryside, for us whose lives are lived in the modern city.

My experience of them is that they have always just gone as you arrive, or are due but nobody quite knows when. They are elusive, like whales or otters or foxes. You never see them when you go on the special whale or otter-watching tour. But they appear, out of the blue, when they want to. Driving along in a car in the deep winter stillness of St Stephen’s Day, the wren boy of Toomevara seemed to me like one of those envoys from another world, from the wilderness or the past. You feel lucky when you catch a glimpse of such creatures. You feel singled out, in a moment out of time. You feel blessed. Then you move on.